Venezuela’s loss of thousands of oil workers has been other countries’ gain

Jul 19th 2014 | BOGOTÁ, CALGARY AND CARACAS | From the print edition

IN

2003 Venezuela’s then president, Hugo Chávez, fired more than 18,000

employees, almost half the workforce, of the state-run oil corporation,

Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). Their offence was to have taken part in a

strike (pictured) called in protest at the politicisation of the

company. Their punishment was to be barred from jobs not only in PDVSA

itself but also in any company doing business with the oil firm. The axe

fell heavily on managers and technicians: around 80% of the staff at

Intevep, PDVSA’s research arm, are thought to have joined the strike. At

the stroke of a pen, Venezuela lost its oil intelligentsia.

It

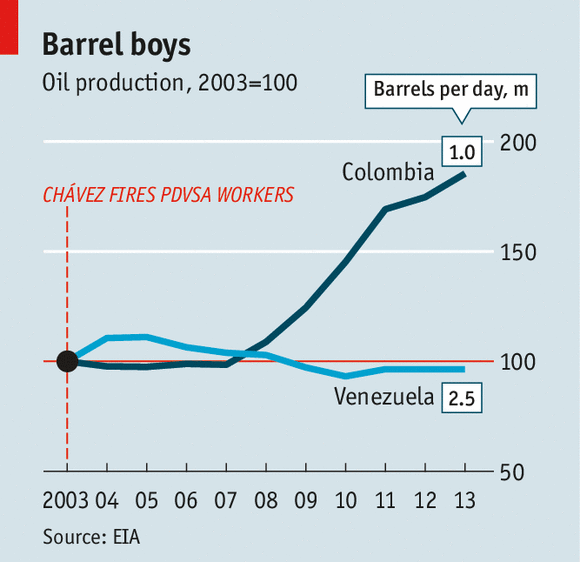

was a blow from which PDVSA has never recovered. The firm’s oil

production has since stagnated (see chart), despite a big run-up in

prices. The financial crisis bears some of the blame for that, as does

the economic mismanagement of Chávez and, since last year, Nicolás

Maduro. But the loss of skilled personnel was a huge handicap, hurting

exploration and management. The Centre for Energy Orientation, a

Venezuelan NGO, says the number of incapacitating injuries due to

accidents at PDVSA rose from 1.8 per million man-hours in 2002 to 6.2 in

2012. At Pemex, Mexico’s state oil firm, the rate was 0.6 in 2012.

Venezuela’s

loss was others’ gain. Not all of the former PDVSA employees stayed in

the oil business; a minority chose to remain in Venezuela. But thousands

went abroad—to the United States, Mexico and the Persian Gulf, and to

farther-flung places like Malaysia and Kazakhstan.

Many headed to Alberta, in Canada, where

the tar sands yield a residue that is similar to the heavy oil from the

Orinoco belt, which Venezuela is struggling to develop. There were 465

Venezuelans in Alberta in 2001; by 2011 there were 3,860.

Pedro Pereira, who once headed PDVSA’s

research into the processing of extra-heavy crude oil, came to Canada in

order to set up a similar research team at the University of Calgary in

Alberta. His work focuses on inventing and patenting new technologies

to process Alberta’s crude. Three dozen Venezuelans have passed through

the Calgary centre since its inception, around two-thirds of them as a

direct result of the purge of 2003. All have gone on to work in the

Canadian oil industry.

No country has benefited more from the

Venezuelan exodus, however, than one next door. Colombia’s oil output

was declining at the time of the purge, falling from 687,000 barrels a

day (b/d) in 2000 to 526,000 five years later. Today, average daily

production stands at around 1m b/d. Much of this renaissance is thanks

to the Venezuelans.

Former PDVSA executives had been heading to

Colombia even before the purge. (Luis Giusti, a former chairman who

quit as soon as Chávez came to power in 1999, helped the Colombian

government redesign its energy policies.) But it was the post-2003

influx that revolutionised the industry. All of a sudden, says Alejandro

Martínez of the Colombian Petroleum Association, “Colombia was filled

with real oilmen.” The Venezuelans had years of experience, lots of it

spent abroad. They had an excellent technical heritage: PDVSA was

created in the mid-1970s when the local subsidiaries of sophisticated

firms like Exxon and Royal Dutch Shell were nationalised. They were also

used to thinking big. “They did not shy away from projects that needed

$2 billion in investments when for Ecopetrol [Colombia’s state oil firm]

$50m was a big deal,” says Mr Martínez.

In 2007 Ronald Pantín, a former chairman of

PDVSA Services, bought Colombia’s Meta Petroleum along with several

partners. Meta operated the Campo Rubiales field in central Colombia,

from which operators were then barely squeezing 14,000 b/d. Now it is

the country’s largest producing oilfield, and Pacific Rubiales Energy,

Meta’s owner, is the largest independent oil producer in Colombia.

Humberto Calderón, a former Venezuelan oil minister, founded Vetra in

2003. Today the two firms account for more than a quarter of the

country’s production.

Without the input of the Venezuelans “there

is no way Colombia could have doubled its production in such a short

time,” says Carlos Alberto López, an energy analyst. It was an

“extraordinary coincidence” that Colombia carried out its reforms just

as PDVSA’s managers were thrown out, oil prices soared and areas once

under guerrilla control were made safer. “The timing couldn’t have been

better,” says Mr López.

The prospects for enticing the diaspora

back to Venezuela are poor. The expatriates have put down deep roots

abroad, and the situation at home remains chaotic. PDVSA’s goal is for

the Orinoco belt to be producing 4.6m b/d by 2019. But the oil is

difficult to refine, and the huge investment required is hampered by the

government’s insistence on overvaluing the bolívar. So far PDVSA has

missed all its intermediate targets for Orinoco: by the end of 2013 it

had reached 1.2m b/d, compared with a planned figure of 1.5m.

Welders,

electricians and machine workers reportedly make three times as much

helping with the expansion of Ecopetrol’s refinery in Cartagena as they

can in Venezuela, according to El Nacional,

a Venezuelan daily. A ranking published by Hays Oil and Gas, a

recruitment agency, put the average annual salary for oil-industry

professionals in Colombia at $100,300. In Venezuela it is $50,000. From

Calgary Mr Pereira says he is seeing a “second wave” of emigration that

began a couple of years ago, of young professionals with five or six

years’ experience. “As soon as they get some significant knowledge,

they’re leaving,” he says. “The company, and the country, is heading for

a disaster.”

No comments:

Post a Comment